The goodwill that game engine developer Unity burnt over the last week with its bizarre and retroactive pricing demands are going to be a problem for not just the iPhone, but Apple Vision Pro too.

Given Unity’s lynchpin status for Apple, it’s important to understand what’s at stake here. If you’re not familiar with them, Unity is a featured Apple Vision Pro development partner and the maker of a game engine whose tech powers many of the top-selling games on the App Store.

Unity recently announced new licensing terms for its software, immediately meeting fierce backlash from developers and sending the company into crisis management mode. Now it looks like Unity will reset its plans.

What is Unity?

Unity Engine helps devs make 3D games and apps. It’s one of the most popular game engines out there: Unity claims to be at the heart of more than 60% of the top-grossing mobile games on the iPhone.

Unity is used by AAA studios and independent game makers alike, the basis of games like Niantic’s Pokemon Go and Blizzard Entertainment’s popular game Hearthstone, even Ustwo’s award winning isometric puzzler Monument Valley.

Unity’s origins began at a business called Over the Edge Entertainment, formed around 2002 to make an open-source 3D game engine for the Mac.

Their proof of concept was a game called GooBall, a Super Monkey Ball-style maze runner featuring an blobby alien floating in a jiggly, transparent ball of goo. Mac shareware darling Ambrosia Software brought the game to market.

GooBall didn’t exactly set sales charts on fire, but Over the Edge Entertainment already had much grander plans than just to develop Mac games.

They branded the core engine tech they’d developed as Unity and presented it at WWDC in San Francisco in 2005 (they even got a runner-up Apple Design Award the following year). Unity initially targeted Mac OS X, later adding support for web-based games and Windows.

Unity — by then, the brand adopted by both the company and platform — was there when Apple introduced the App Store for the iPhone, and has figured prominently on Apple platforms since. Unity works on a lot more than Apple devices, of course, promising “write once, deploy anywhere” (more than two dozen platforms, at last count).

Why are developers mad?

Up until this announcement, Unity’s pricing was pretty straightforward: a free personal tier for hobbyists, students, and devs just wanting to kick the tires, with per-seat annual licensing set at $400 to $1,800 per seat depending on the size of the business. Enterprise licensing was also available.

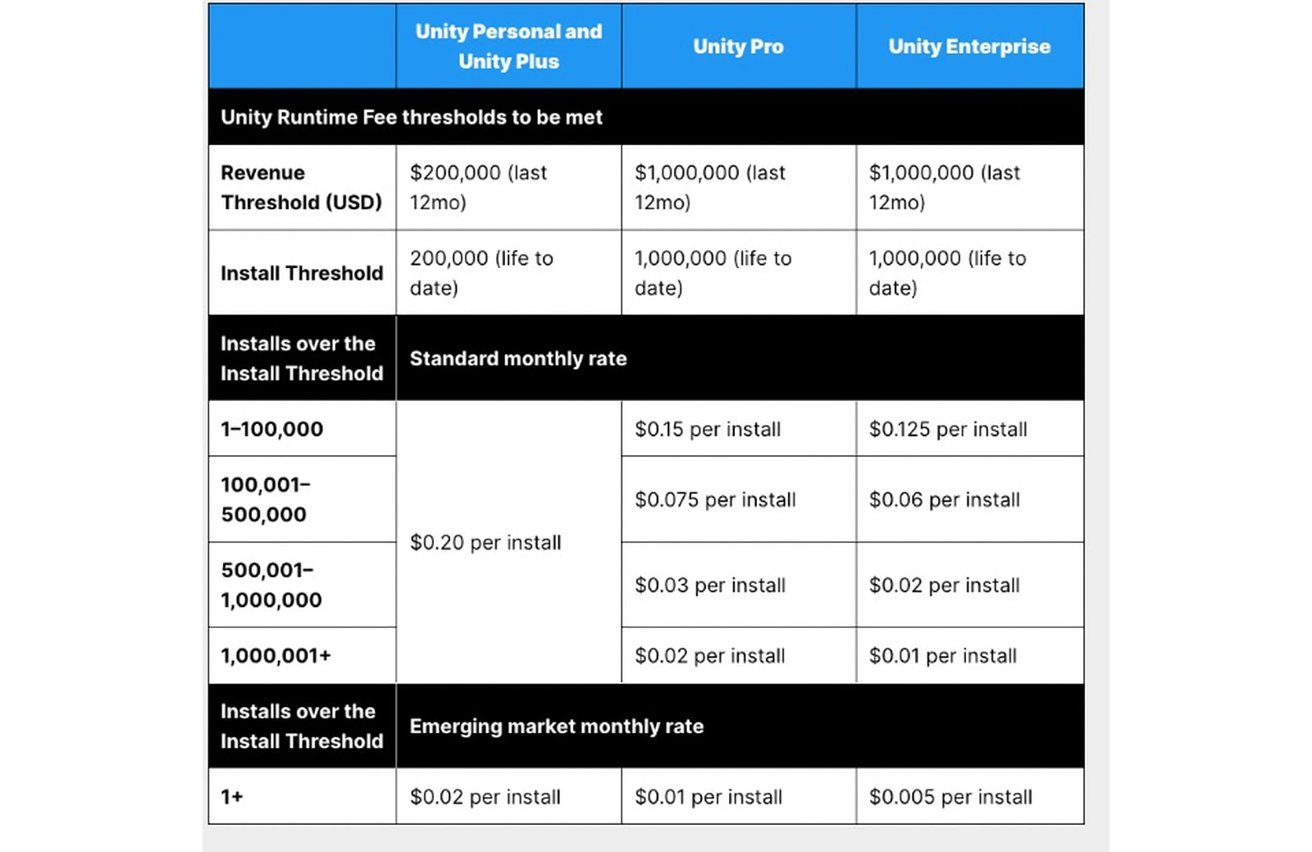

In mid-September Unity announced a revamp of its licensing model, switching to a pay-per-download pricing scheme. The license would incur fees of up to $0.20 per installation, once developers hit specific revenue and download number thresholds.

Unity tried to sell this as a benefit to its customers.

“We believe that an initial install-based fee allows creators to keep the ongoing financial gains from player engagement, unlike a revenue share,” said Unity on its blog.

Unity later tweeted that the change would impact fewer than 10% of their customers.

“Customers who will be impacted are generally those who have found a substantial scale in downloads and revenue and have reached both our install and revenue thresholds,” they wrote. “This means a low (or no) fee for creators who have not found scale success yet and a modest one-time fee for those who have.”

Developers weren’t having it, raising questions about numerous edge cases like charity bundles, fraudulent or pirated installs, sales through game services like Xbox Game Pass, “install-bombing” (to punish marginalized developers) and other situations that Unity either ignored or didn’t think much about ahead of time.

Unity’s plans to track installations using its own proprietary system also raised red flags. That, combined with Unity’s vague language and repeated clarifications in the following days only made things worse.

Analyzing sunk cost

Some devs threatened to pull up stakes from Unity altogether and go to the competition, including Epic’s Unreal Engine and open-source engine Godot.

This is easier said than done. Game engines are foundational technology, and replacing one can mean scrapping a game and starting over.

If you’re already three or four years into a game development cycle — as some of the most vociferous developers are — switching now is almost an impossibility. The other problem is, switch to what?

Unreal Engine is a possibility for some developers with the teams and the skill to make it work, but it’s a much more unforgiving environment and not particularly cheap, either.

There’s Godot and a few other open-source game development tools, but Unity’s got almost two decades of runway behind it, a huge number of developers who already know the environment, and tons of tools that work with it.

There just isn’t a lot out there to replace Unity, a fact not lost on Wall Street analysts. Some analysts acknowledged the public relations debacle but still saw upside potential for the company’s stock, precisely because many developers won’t have a choice.

Some developers are resigned to paying whatever Unity will charge them beginning in 2024. Some are looking at the company with increased skepticism and wondering where to go from here.

The ire over the new licensing scheme reached an absurd and terrifying crest a few days after the announcement when Unity closed several offices and cancelled a planned town hall meeting with its CEO following a “credible death threat.”

Compounding the chaos, reports have emerged that the threats may have been made by a Unity employee working in a field office (the company is based in San Francisco).

The long-term damage to developer trust may be permanent, but we’ll see. What pretty much everyone can agree on is that Unity really stepped in it, and didn’t make anyone happy.

“We f…ed up on many levels” — Unity founder

On Monday, a contrite Unity admitted it had made a mistake in a tweet.

“We have heard you. We apologize for the confusion and angst the runtime fee policy we announced on Tuesday caused. We are listening, talking to our team members, community, customers, and partners, and will be making changes to the policy,” said the company.

A Unity spokesman quoted in the article claims that the company will instead rely on customers to self-report installation data. This would defuse one of the more explosive aspects of the new policy, Unity’s own proprietary install metrics.

Some details remain to be worked out as Unity takes the novel approach of actually working with stakeholders this time, rather than springing a very unwelcome surprise on them.

“I don’t think there’s any version of this that would have gone down a whole lot differently than what happened,” Unity CEO John Riccitiello is reported to have said during a company meeting to discuss the changes. “It is a massively transformational change to our business model.”

Unity co-founder and Riccitiello’s predecessor as CEO, David Helgason, took to Facebook over the weekend and stated more plainly, “We f…ed up on many levels.”

Describing the runtime fee as “a new business model for Unity,” Helgason admitted the company had “missed a bunch of important ‘corner’ cases.”

The new arrangement “ended up as the opposite of what it was supposed to be,” he said.

AppleInsider reached out to Unity for comment but had not heard back as we went to press with this article.

Lots of growth but still no profit

Unity brought in more than $1.4 billion in revenue in 2022, a more than 25% year over year increase, and is on track to bring in more in 2023. But despite the revenue growth, Unity isn’t making a profit, and actually never has.

“Unity lit money on fire for decades to buy a market advantage that overrules the basic economic incentives that supposedly ensure free markets work best for customers. It was successful in doing that because it’s very hard for a sustainable business to compete against one that is fine losing billions of dollars,” wrote GameIndustry.biz’s Brendan Sinclair.

So it’s perhaps understandable why its leadership, under the aegis of EA’s former top dog, John Riccitiello, has sought to change things up.

Unity is a lot more than just a game engine these days. It’s made a number of strategic acquisitions over the years including ad tech for mobile games, game streaming, and more. The company has branched out vertically into television and film, the automotive industry, architecture and other markets, spending more than $1.6 billion to acquire Weta Digital, the visual effects studio that brought the Lord of the Rings and Avatar movie series to life.

A 2022 stock swap deal with adtech firm ironSource valued at $4.4 billion dwarfed the Weta acquisition, and cemented Unity as an end-to-end development and business platform for game makers. But ironSource was a controversial choice for Unity.

The company’s first product, InstallCore, was used to bundle and install unwanted software on Windows PC, ultimately getting flagged by Microsoft’s own Windows Defender software as malware.

IronSource rival AppLovin attempted to spike the deal with a $20 billion acqusition bid for Unity that Unity ultimately rejected, seeing the ironSource deal as a better value proposition.

Now Unity appears poised at AppLovin’s throat.

Following the unveiling of the new licensing scheme, Unity is offering some customers a waiver if they agree to use LevelPlay, the rebranded ironSource technology, according to a report from Mobilegamer.biz.

Riccitiello himself raised eyebrows for questionably timed recent stock sales: He’s sold more than 50,000 shares this year, including a 2,000 share transaction that happened just a week before the runtime fee announcement.

Unity’s also gone through several rounds of layoffs, axing more than 500 workers in two rounds of layoffs in 2022 and 600 more earlier this year, or about 8% of its total headcount.

Riccitiello himself has been a lightning-rod for controversy in the past. Last year he apologized after calling game developers who don’t focus early on monetization “my favorite people in the world to fight with — they’re the most beautiful and pure, brilliant people. They’re also some of the biggest f…ing idiots.”

Those words are coming back to bite Riccitiello in the posterior as developers push back against Unity’s own monetization efforts.

Unity and Vision Pro

Unity remains a key development partner for Apple, just as they’ve been since their debut in 2005. That factors not only into the platforms Apple offers today but the one to come as well: Vision Pro.

In unveiling Vision Pro at WWDC 2023, Apple said that Unity would be there with app development tools. Unity followed through only a few weeks later when they launched a developer program.

Unity R&D VP Ralph Hauwert and Apple Technology Development Group VP Mike Rockwell discuss Vision Pro at WWDC 2023

The company introduced plug-ins and other tools to make it easy for existing Unity developers to build apps that work on Vision Pro. Unity has branded its new tools “PolySpatial” technology, promising the ability to make apps that can run “side by side” in Vision Pro’s “Shared Space.”

Developers don’t need Unity to make apps or games for Vision Pro. But Unity is still an important ally for Apple because of its popularity and familiarity for many developers, including many who otherwise might not target Apple operating systems.

So far, there hasn’t been any word from Apple on the Unity situation, and there isn’t likely to be. But Cupertino is surely watching and talking with them behind the scenes.

Ironic name

Time will tell if the revamped plan the company is now working on will make its customers any happier. Similarly, we’ll see if there’s a mass exodus of developers away from Unity, or just a trickle.

One thing’s for sure. Unity’s initial run at revamping its licensing structure was, by any measure, a complete PR disaster. The company executed the news poorly, communicated it badly and, it seems, didn’t even think it out particularly well.

Ironically, the only “unity” that developers feel seems to be enmity against the very company they’d grown to trust.

The trust is going to take a lot longer than a week and a few mea culpas for Unity to earn back.